From the MPL Archives: 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic Signs

|

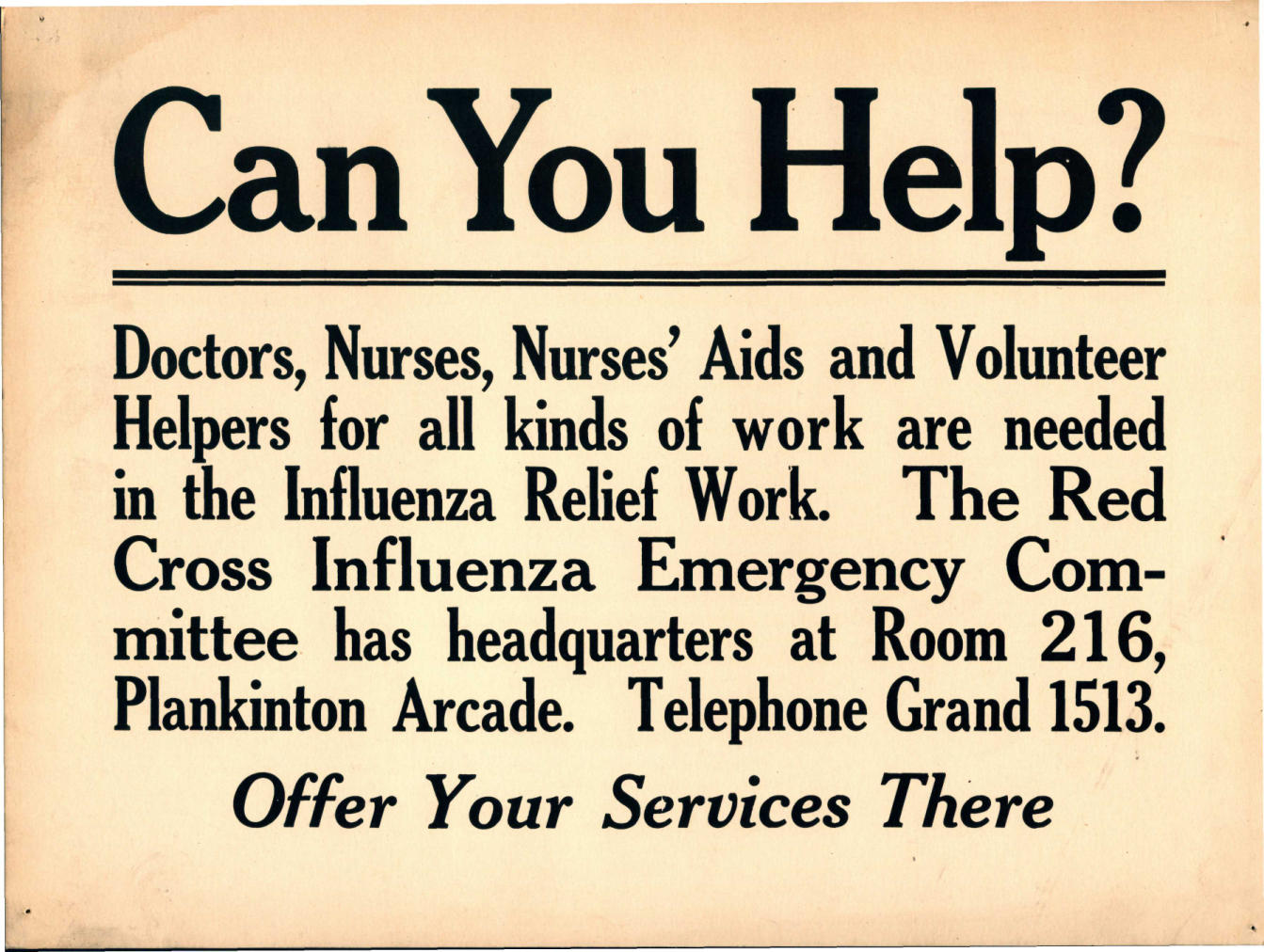

| Plankinton Arcade, 1924, Milwaukee Public Library, Historic Photo Collection |

I had a little bird,

its name was Enza,

I opened up the window,

and in flew Enza.

—Children's ditty, Fall 1918

John Gurda wrote about the lessons learned from the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic in his March 29th column in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee County Historical Society archivist Kevin Abing wrote an extensive article on how our city fared from and responded to the pandemic at Milwaukee Independent and in the spring issue of Milwaukee County History.

Philadelphia was especially hard-hit, with 12,191 influenza deaths in a five-week period, (837 on October 12th) from late-September to early-November 1918. Milwaukee had the lowest, or one of the lowest, large city influenza pandemic mortality rates, depending on the time span. The 1918 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health of the City of Milwaukee recorded 1,108 city residents died from influenza during the September-December pandemic.

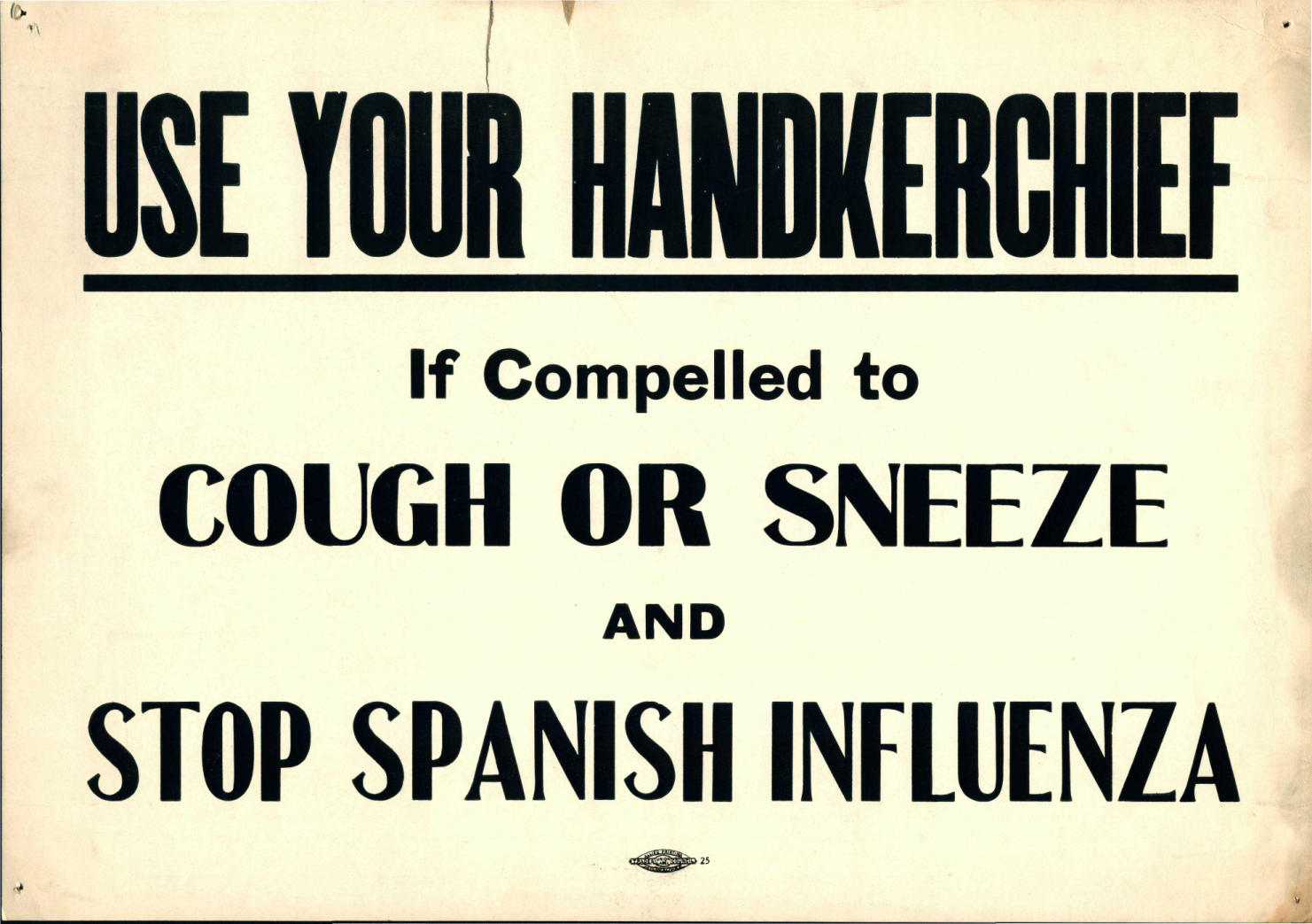

Our Local History Manuscript Collections includes the Milwaukee County Council of Defense Records, which has two signs from the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic.

|

The first sign told people to cover their coughs and sneezes to stop spreading the "Spanish Flu." The first recorded outbreak of the pandemic was at Fort Riley, Kansas in March 1918 during World War I. American doughboys (soldiers) carried the virus across the Atlantic to France where it spread in the trenches on the Western Front. Both sides of the war largely suppressed news of the worsening pandemic among soldiers in an effort to keep the enemy in the dark. Spain stayed out of the war and their press reported the rising toll of infections and deaths in Europe. This led the world to call the worsening pandemic, the "Spanish Flu," even though it didn't start in Spain.

To get a sense of how deadly the 1918-1919 pandemic was, about 50,000,000 died from influenza. 16,000,000 combatants and civilians were killed in World War I (1914-1918). 116,516 Americans died in World War I (1917-1918). 26,277 doughboys were killed in the Meuse-Argonne (September 26th-November 11th, 1918), the deadliest battle in U.S. military history, which coincided with the deadliest month (October) of the pandemic on the home front. Influenza killed an estimated 45,000 doughboys and jackies (sailors). 675,000 Americans died from the 1918-1919 pandemic.

|

The "Can You Help?" sign was a Red Cross Influenza Emergency Committee campaign to recruit doctors, nurses and volunteers for its pandemic emergency work, such as making masks. Their Motor Corps drivers transported patients to hospitals, and delivered food and supplies. The office was in the Plankinton Arcade, which opened in 1916, decades before it became part of the Grand Avenue shopping center in 1982. The Red Cross telephone number was Grand-1513.

If you're wondering, the phone number of the Milwaukee Health Department was Broadway-3715 and the Milwaukee Public Library's phone number was Grand-2686.

As the pandemic worsened, Milwaukee Health Commissioner George C. Ruhland almost closed the city on October 17th. In the Library-Museum Building (Central Library), the Milwaukee Public Museum (west and north wings) closed. The Milwaukee Public Library's (east and center wings) Reference and Children's rooms closed, but the Catalogue and Delivery rooms remained open for book checkouts. The next day, he closed MPL's nine branches, Detroit, East, Lapham, Lisbon, Llewellyn, North, South, 3rd St. and West Division High School.

As the pandemic loosened its grip, Ruhland reopened the Milwaukee Public Library and Milwaukee Public Museum on November 4th. Influenza continued to reap lives with its scythe on a smaller scale as Milwaukeeans celebrated the end of what was then called the World War on November 11th, then a second wave of infections and deaths surged around Thanksgiving.

Ruhland responded with a partial closure of the city on December 7th that was extended to the Milwaukee Public Library and Milwaukee Public Museum four days later. When infection and death rates returned closer to more normal levels, he lifted restrictions in stages on Christmas Day and January 2nd, 1919.

Dan, Local History Librarian